New book uncovers the inconvenient truth of Nazi collaboration

Above: Anzac Guerrillas by Edmund Goldrick (right). Image: https://www.library.gov.au/whats-on/events/book-launch-anzac-guerrillas-edmund-goldrick

By the time Canberra-born historian Edmund Goldrick began sifting through the footnotes of Balkan military history, he expected to find contradictions, propaganda, or maybe even a few disputed battlefield wins.

What he didn’t expect and what ultimately set him on the path to Anzac Guerillas, was to look at an ordinary Australian Anzac Day march and uncover in the banners of a Serbian émigré group, the same royalist symbols once carried by men who had cut deals with the Third Reich.

Goldrick’s meticulous four-year investigation and two and a half years of writing, spanning five national archives and a literal tonne of declassified intelligence, reconstructs a story Australia had all but misplaced: How two young Australians, caught in the undertow of World War II’s most bewildering front, stumbled onto evidence that the Serbian royalist Chetniks, who though long mythologised as Allied heroes, were since 1942, working together with Nazi forces.

US Newspaper clipping, 1946. Wikipedia.

The book opens in the mountainous interior of occupied Serbia, where Ronald Jones, a 24-year-old from Victoria’s working-class Richmond, was on the run, having survived German-occupied Crete only to be packed onto a German transport train, from which he leapt into the night and disappeared into a landscape of ruins and rivalries that few outsiders, even then, could decipher.

Jones expected anti-German partisans, patriots, a resistance with purpose. What he found instead was General Draža Mihailović, the exiled Yugoslav royalist commander celebrated in Allied newspapers as a Balkan Robin Hood.

But the scenes Jones witnessed under Chetnik protection such as passivity before German patrols, whispered deals, coordinated strikes against communist Partisans and at times, open collaboration, told a different story.

Above: Serbian Chetniks posing with the German Allies, eastern Bosnia, 1943. Wikipedia.

Moreover, writes Goldrick: “Mihailović himself had told Jones that he planned to wait until the war was over and then to “clean” Greater Serbia of all but ethnic Serbians. These days we’d call it genocide.”

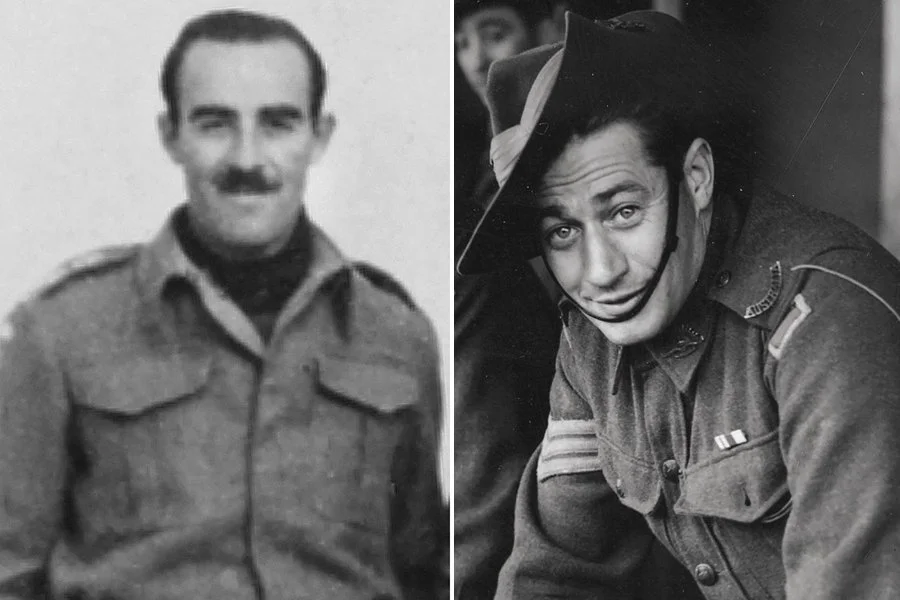

Hours to the south, Ross Sayers, a miner from Castlemaine, also in Victoria, too was swept into Chetnik ranks — not by choice, but by a rifle barrel wielded by a Chetnik major by the name of Dragutin Keserović, whose fiery speeches masked a grim pattern of summary killings.

By 1943, Sayers had been folded into Churchill’s Special Operations Executive, tasked with separating truth from legend inside Yugoslavia’s resistance movements. From Chetnik territory, his early reports echoed Jones’ grim warnings: Mihailović’s forces were coordinating with German units to contain Tito’s fast-growing Partisans.

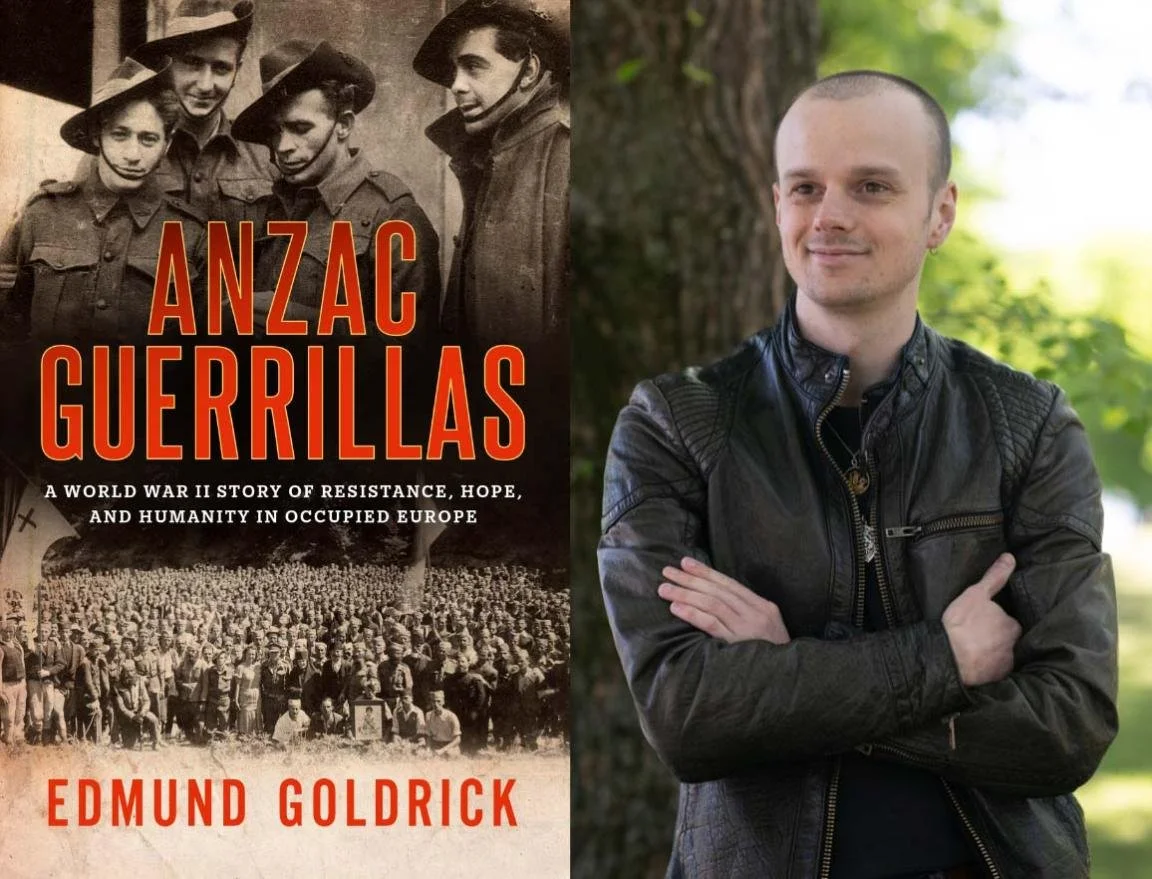

Ronald Jones (left) and Ross Sayers (right). Image: https://citynews.com.au/2025/historian-recounts-harrowing-tale-of-aussie-pows/

Goldrick’s archival work makes clear that this wasn’t rumour but routine. He traces German field reports, decrypted radio traffic, and local agreements in which Wehrmacht officers carved out quiet zones for the Chetniks in exchange for intelligence on Partisan movements.

It was a marriage of convenience, born of fear, that is, the Germans feared Tito’s guerrillas far more than Mihailović’s Chetnik irregulars.

Jones, meanwhile, fell into Italian custody, endured torture and three prison camps, escaped yet again, and surfaced in Switzerland long enough to deliver an intelligence memorandum flatly accusing the Serbian Chetniks of betraying their countrymen under the banner of royalist legitimacy.

Jones believed that memo helped turn British policy. But Goldrick’s sober assessment is more painful: almost no one in London read it. Decisions had already begun shifting because of the Ultra decrypts, which painted collaboration in stark, unignorable terms. By late 1943, Churchill abandoned the Chetniks and placed Britain’s bets on Tito.

Sayers, (top left standing) with Serbian Chetniks. Image: Gippsland Times.

History vindicated the Australians’ instincts. Mihailović was captured in 1946, tried for treason and collaboration, and executed. Yet the men who had seen collaboration firsthand received no such resolution.

Jones returned to Melbourne and folded into anonymity, rarely speaking of Serbia again.

Sayers returned angrier. He refused to march on Anzac Day, perhaps recognising, in Serbian Chetnik veterans’ groups, the same royalist insignia he had seen flying beside German units.

He and his wife Mavis died together in 1982 in a boating accident.

Above: Chetniks marching on Anzac Day, Sydyey 2013.

Goldrick’s book is unique because he has asked the question many others – including Australia’s Returned Serviceman’s League (RSL) have deliberately ignored.

In other words, how could symbols once carried by documented Nazi collaborators end up side-by-side at a national march honouring Australian sacrifice and bravery?

The answer, Anzac Guerillas shows, is equal parts lost memory, political mythmaking, and the fog of a war where yesterday’s enemy was often tomorrow’s ally — and sometimes both at once.

For their part, at the time of publication, the RSL has flatly refused to publicly comment on the revelations uncovered by Anzac Guerillas, despite promoting the book on its own Facebook page and in various RSL venues around the country.

Their attitude to what is a very inconvenient truth seems to be directly in opposition to their stated goals of honouring the Anzac spirit.

Serbian Chetniks - in WW2 and now in Australia.

Goldrick writes with the restraint of a researcher and the instincts of a reporter. His portraits of Jones and Sayers are empathetic without hero-making, and his reconstruction of wartime Serbia — a landscape of uneven loyalties and impossible choices — is one of the finest now available to general readers.

But what lingers is the shock of the discovery itself: that forgotten Australian soldiers had once risked their lives to expose Nazi collaboration — and that decades later, in suburban Anzac marches, the descendants of those collaborators still to this day walk in the same parades, unchallenged.

It is perhaps no coincidence and deeply unsettling that, more than eighty years later, Australia is again confronting public displays of Nazi ideology.

Above: National Socialist Network (NSN)

In November 2025, about 60 men from the National Socialist Network (NSN) gathered outside New South Wales Parliament, clad in black, chanting the Hitler Youth slogan "blood and honour" and waving a banner demanding, “Abolish the Jewish lobby.”

One of the men pictured was Matthew Gruter, a South African national whose visa was cancelled by the federal government on the grounds that he had participated in a hateful, ideologically driven rally.

Meanwhile, far-right figure Joel Davis, linked to the NSN, was denied bail after allegedly sending threatening messages to federal MPs following their condemnation of the rally.

It’s highly likely that Edmund Goldrick didn’t intend to write Anzac Guerillas as a comment on contemporary extremism. But as he uncovered long-hidden ties between Chetnik royalists and Hitler’s Wehrmacht, his narrative gained new urgency. He reminds us that ideological compromise and moral ambiguity are not relics of the past — they are present, persistent.

Above: Neo-Nazis outside NSW Parliament, November 2025. Source: Australian Jewish News

Through Jones and Sayers, Goldrick offers more than a story of survival: he presents a moral reckoning. These were men who believed in royalist, anti-communist ideals—and yet found themselves witnessing collaboration with the Nazis.

These two Australians courage was not just physical, but intellectual: they refused to accept simplistic narratives, even when doing so made them unpopular with their commanding officers.

In modern Australia, as neo-Nazi groups exploit public spaces – both online and physical in order to test the limits of free speech, Goldrick’s book has become a vital reminder of what the Allies fought for and against.

Thomas Sewell, Australia NSN leader and fellow neo-Nazis.

The symbols fluttering at the annual Anzac Day marches, or at public rallies may carry deeper shadows than many realise. Anzac Guerillas asks us to confront them, to question, to remember, and in the end, to refuse the erasure of inconvenient truths.

Anzac Guerillas ultimately is a reminder that the stories Australians have enshrined about Anzac Day are never as simple as the banners suggest, and that sometimes the past isn’t buried, but rather that it’s hiding in plain sight.

Anzac Guerillas by Edmund Goldrick is published by Hachette Australia.